One Year Without a Smartphone: Limitation is the new Liberation. Breaking free from digital dependency and living truly Super Connected

Wow. One year without a smartphone.

The Decision to Go Smartphone-Free. For Good

What was it like? Well, it wasn’t easy, but it wasn’t so difficult that I’m going to go back to a smartphone. I’m not. Regular readers will know I’ve been working towards this ever since I began writing the songs for Super Connected. Finally, I made it.

So the iPhone is staying in the cupboard. I’m sticking with my Light Phone, which, in its unique way of having hardly any features at all, has brought back my concentration to a greater level, as well as the ability to appreciate space and time to think and reflect, as opposed to constantly acting on ideas or responding to the endless amounts of suggestions, mindless information and news that come through a smartphone.

Don’t get me wrong, when I’m at my workstation, I am ‘wired in’ like Jesse Eisenberg in his portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg in the Social Network. But as soon as I am up and moving, travelling or out and about, I’m not wired into anything. Apart from myself and the people I am sharing space with.

“Learning to choose is hard. Learning to choose well is harder. And learning to choose well in a world of unlimited possibilities is harder still, perhaps too hard.” - Barry Schwartz

The Paradox of Choice

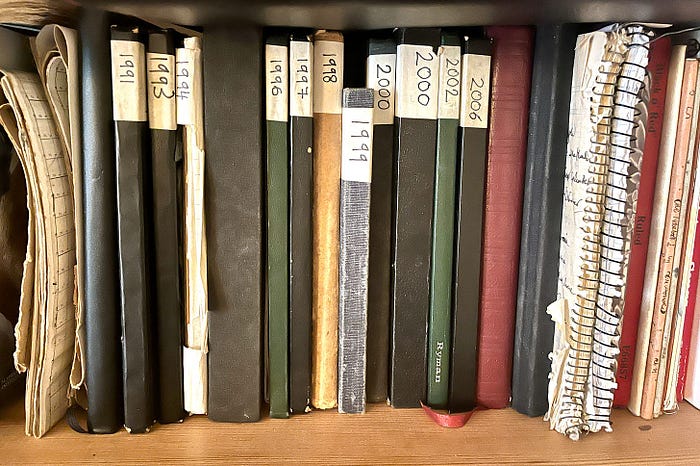

Looking back through my lyric books from the peak years of my smartphone use — roughly 2012 to 2022 — I’ve noticed something striking. The sheer volume of songs I’ve written in the past year without owning a smartphone, far exceeds my annual creative output during those ten years.

In fact I took a look through my early lyric books from age fifteen to twenty two — my most prolific period which amassed enough songs to make my first 10 albums. The last year without a smartphone is the same.

My smartphone gave more choice, more rabbit holes of information. But without it, I am capturing and completing the ideas instead of only capturing them. Less choice has resharpened my ability to stay focused on my creative intentions.

The Phantom Limb Effect

My improved attention and intention has a lot to do with the Light Phone. By having less ‘built in productivity’ in itself, the Light Phone has made me more productive.

One thing I will admit though — I don’t think my addictive bond with the smartphone has actually gone away. Even though I’m not using it and haven’t used it or carried it in my pocket for a year, sometimes I will reach for my Light Phone in my pocket as if it were a smartphone, without a reason. I take it out of my pocket and stare at it before realising there’s nothing I can scroll through and nothing I can look at.

The ghost of my iPhone is still in my pocket. After a year.

I had it bad.

It made me realise that, for me, the attachment to my smartphone when I was using it, was very much to do with my emotions. An emotion of feeling connected that came through the fusion of world news or information from strangers online, mixed with personal communication with actual friends. A digital cocktail of convenience that brought as much dopamine delight as dopamine depletion.

It was actually harder to give up my smartphone than it was for me to recover from drug addiction, 22 years ago at a Buddhist Monastery in Thailand.

Real vs. Simulated Connection

I’ve also noticed that using a smartphone, in my experience, used to be a way of expanding the amount of connection I felt to other people — whether I knew them or not. As a performer who has worked on stage my whole life, I’ve been used to meeting and greeting people I do not know very well. So doing it on social media was never something I thought deeply about in the beginning. Eventually I did.

I began to understand that I didn’t actually have a connection with them. I felt a connection. This is the distinction that many of us often fail to see and, whilst this collective myopia benefits big tech, it has had a cataclysmic impact on families.

The ‘feeling’ of being connected is actually a representation of the feeling…

rather than the thing itself.

But, and I say this with the fortunate experience of having lived in a Buddhist monastery with monks for several years in Thailand — this representation is actually an illusion — the ultimate distraction from a true path of spirit that I believe all of us would choose, if we could find our way onto that path.

True connection is not simply about numbers or access, but about something more tangible, rooted in presence, shared experience and a felt sense of being.

One of the spiels I poke fun at on the Super Connected album is the constant messaging and PR from tech companies and entrepreneurs about how ‘connected we all are’.

Communities, movements, groups, collectives — tech loves the ‘tribe’. But a tribe full of individuals who can connect to others but not their individual selves, is a tribe whose strength empowers the ‘host’ of that tribe, not the tribe itself. Hello Meta, Amazon, Spotify and X.

The lords of Silicon Valley really know their ‘people’. But they don’t know, and don’t need to know, any single individual spirit. And if we spend the early years of our lives on a constant digital diet of gift-wrapped screen-tinted eye candy, what chance will we ever have to get to know our own spirit?

Categories and genres are what big tech needs. Because categories and genres hold substantial numbers, which can be traded on with third party advertisers. So it feels good not to carry that spirit-destroying device in my pocket anymore.

The Practical Side of Being Smartphone-Free

I’ve been asked on many occasions by friends if not having a smartphone presents problems, like tickets and QR codes or Ubers. It’s a valid question because I am aware that, for most people, these would be enormous challenges. I have not experienced many of these challenges, mainly because I do not go out into commercial spaces very often, and I really struggle with coming into contact with the environment of modern restaurants or service venues, (with the exception of cinemas, theatres and my own shows). So going without a smartphone has not presented challenges for me.

As a non-driver, I do a lot of walking and riding on my Brompton Bike. When it comes for packing more than one guitar and all the stage gear for Super Connected, I call a local cab firm who rather nicely remember my name and I do not feel locked into the chop-block of an app. It’s a preference to support local businesses as well.

For airplane tickets, trains, and the odd exhibition, I still use a printer and I have a little lanyard that I fold up tickets in. Paper is still accepted pretty much everywhere.

“But it’s so much easier doing it on a smartphone”

I agree, it is easier. Every time you use a smartphone, it just gets easier and easier doesn’t it? And if that is appealing, then smartphones are great.

It’s just not what I’m looking for while I’m living this gift we get called life.

Digital Minimalism Is Contagious

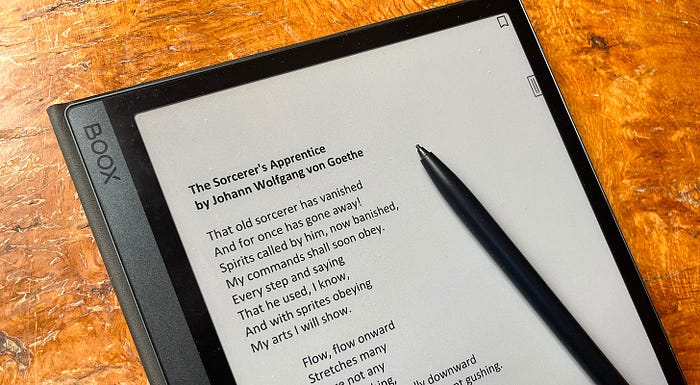

Moving to the Light Phone led to something unexpected — it made me rethink my whole digital life. The Light Phone’s E Ink screen made me realise how intense regular screens were. Within six weeks, my eye strain reduced.

That led me to get an E Ink tablet — the BOOX Tab C Ultra Pro. Now, instead of staring at a glaring backlit screen, I read and write with a device that works like paper, using the natural ambient light instead of shining artificial light into my eyes. It’s slower to use than my standard Macbook Pro, but for creative tasks when slowing down is useful, it’s the best.

Some readers might think this is ‘Neo-Luddism’, but it’s not at all. It’s not about rejecting technology, it’s about embracing better technology, designed for human beings, rather than human doings (as my mother used to call me at the height of my smartphone usage)

The End of Digital Brain

What I call digital brain — the automatic, unconscious scrolling, tapping, reacting behaviour — has dramatically reduced.

When I used to pick up my smartphone, I rarely did it with intention. More often than not, I’d get caught in a loop — opening one app, then another, then another, forgetting what I even meant to do in the first place. And feeling overwhelmed in the intervals.

As author Jonathan Haidt wrote in The Anxious Generation — the problem isn’t just when we use the smartphone, it’s the intervals in between our usage when we are thinking about what we will use it for as soon as we pick it up again.

That’s all gone now that I use a Light Phone. And that constant preoccupation I felt when I used a smartphone brought nothing to my life whatsoever. But it does bring a lot to Big Tech, which is probably why I ended up writing a screenplay about it and made a film.

Super Connected is the story of how tech-bros are turning us into digital slaves rowing at the bottom of the Silicon Valley Galley ship, with the youngest suffering the most — paid in emojis for their worker-bee roles, as the conquerors up on deck search for new territory in their land grab of humanity. Smartphones are the most successful experiment in ‘customer breeding’ the world has ever seen. Two decades in and only a small percentage of us are asking if children ought to be part of that experiment. Yet it is all of us who are being colonised.

Of course, I still have a main iMac in my music studio, and I have a MacBook for editing all my film projects, but that’s all I really use those for now — unless there’s another complicated task that’s not achievable on the BOOX Tab C Ultra.

The Freedom of Being Mobile and Unreachable

The one thing I’ve loved more than anything else, going smartphone-free, is never being able to be on the internet or be contacted by the internet when I am alone on the move. And for anybody that knows me, it’s probably good to mention that the only way I can communicate with anyone when I’m on the move is: calls or texts.

And I don’t use WhatsApp (A whole other blog that I haven’t written yet!).

So there’s no photos, no audio messages, no social media, emails, pin-drops, links or internet browsing when I travel, not even going to the shop up the road for milk. And this is a huge deal because, it used to make me feel like Superman to be on the move and be so ‘productive’ with the phone in my hand, typing and tapping my life away.

I see one of my neighbours every day take his dog for a walk. But he’s not really taking the dog for a walk. He’s taking his iPhone for a walk and the dog is going along for the ride.

Reclaiming Attention and Imagination

These are sacrifices that I don’t want to change. Because I’m getting to spend more time with my imagination and my emptiness. That’s what I did when I was younger and how I learned to recognise the music and ideas I was carrying inside me, and that’s how my spirit found a way to connect to others. I’m not saying it’s right for everyone, but it’s right for me.

Growing up in the 80s and 90s, I now see my first 25 years of life as a chapter in which I identified what was unique about me and who I am.

Unlike many of my peers, I didn’t grow up with screens. I never played video games as a child — no computer games in the ’80s, no Game Boy or Sony Playstation in the ’90s. In fact, I didn’t use a computer at all until I was 20 (to record music). Yet, when it comes to navigating the internet and using creative digital tools, I am often the one my peers turn to for guidance.

As soon as I started using my first MacBook Pro around 2000 and iPhone in 2008, using screens much more, I can now see that the last 25 years of my life have been getting further and further away from who I am as an individual, and further away from my own nature and from the relationship we all have with the natural world. Instead, I have been bombarded with all the things that the rest of the world tells me I should be, or aspire to be.

Perhaps this was true for many of us in the pre-technology age as well. External forces have been vying for our attention since the industrial age.

But for artists whose vocation is imagining the world differently, it’s much easier to do without the internet and its digital noise attached to your body all day long.

I’ve found these revelations from going smartphone-free alarming, even though I am also a certified Apple Specialist and had an early backstage view of the development of smartphones back in 2010 when I worked at Apple, in London.

But luckily, I began this journey of remodelling my own digital life in 2017. I made the album, the film, the podcast and actually, come to think of it… the T-Shirt too! (Sorry, couldn’t resist it).

I was among some of the first to embrace mobile technology and perhaps also among the first to reconsider it as a life-choice now.

When I first got an iPhone, pretty much nobody else had one, and I was used to people being curious and a little bit sceptical, because they hadn’t moved to a smartphone yet. So it doesn’t really affect me that today, I’m also viewed as a bit of a strange person for not having a smartphone anymore.

A New Digital Norm?

I’m very grateful to new technology like the Light Phone and Boox for creating tools that are, not just innovating technology, but also doing something to maintain, preserve, protect, and facilitate the growth of our human-ness. It’s made me happier. If more people adopt these kinds of devices, it will drive the price down and a new digital norm will be possible that will challenge the stronghold of the current big tech monopoly — a norm that is pervasive and mental quicksand for younger minds.

“Everything that’s popular always starts out as unpopular.” — Vivienne Westwood

Its also helped me back into a renewed appreciation of the natural world, its spirit, and the spirit of other people when they’re able to put their phones down and just witness the wonder of our world without the need to capture it.

I’m getting my sunrises, sunsets, bird watching and tree hugging back, and without hardly ever capturing them on a device.

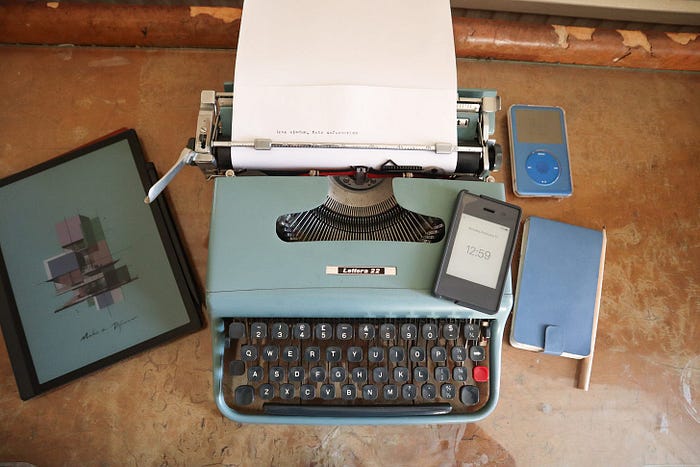

How do I listen to music without a smartphone? With an iPod Classic. The greatest intermediary point between the digital and ‘smart’ age — no logins, no passwords, no ‘paradox’ of choice. Just me, and a limited music library put together with love and patience over time.

We don’t need to go back. Neither do we need to leave the past behind. There’s some good stuff back there, and not just iPods.

For me, limitation is the new liberation.

I expect it’ll be another 25 years before that feels like a popular choice.

But I do believe it could happen.

Tim Arnold, 9th March , 2025

For parents and teachers: We are hosting a live Zoom discussion this April on technology’s impact on young people and how the arts can help. If you’re interested in joining the conversation, you can request a link from our Education Liaison, Guy Holder, at guy@timarnoldcompany.com

If you’ve enjoyed reading this essay, check out The Super Connected Toolkit